THE “BOOGEYMAN” OF BALTIMORE 1951

The summer of 1951 was a weird time in the city of

Baltimore. The city sweltered under a heat wave and only the wealthiest

residents of the region could afford air conditioners at the time. And there

were no air conditioners to be found in O’Donnell Heights, a housing project on

the southwest side of the city. This was a place where steel mill and shipyard

workers lived with their families. For those folks, though, the steamy heat was

less of a worry than the specter that was stalking their streets.

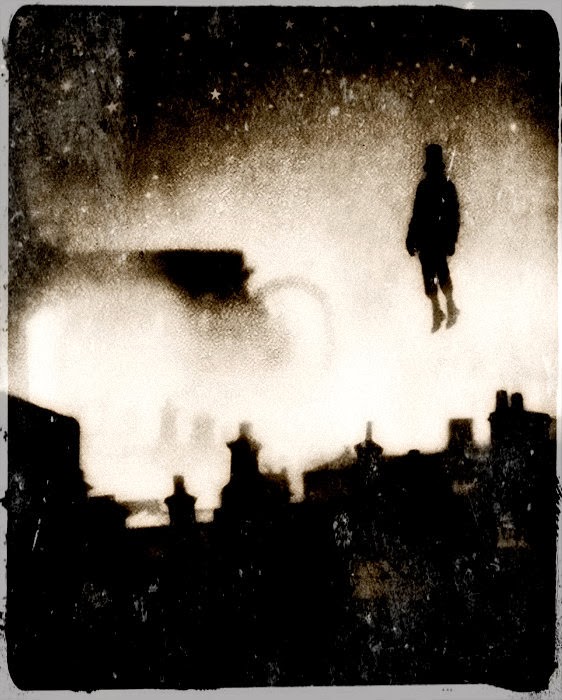

At some point in July, a tall, thin figure, dressed

all in black, began sprinting across the rooftops of O’Donnell Heights. It

leapt on and off buildings, broke into houses, attacked people, enticed a young

girl to crawl under a car and played music in the nearby graveyard. Groups of

young men patrolled the streets, while others waited by their windows at night,

keeping a sleepy watch for the “Phantom Prowler” that eluded his pursuers and

vanished into the cemetery before he could be caught. By the end of the month,

police were arresting people for disorderly conduct and carrying weapons, but

the phantom had disappeared and was never seen again.

What in the hell happened in O’Donnell Heights in

the summer of 1951? To this day, no one knows.

O’Donnell Heights was only eight years old when the

mysterious stranger began making his appearances. Built as a housing project

for defense industry workers at Bethlehem Steel, Martin Aircraft and Edgewood

Arsenal during World War II, it was never meant to be either durable or attractive.

Tightly-spaced, two–story row houses went up on sixty-six acres of what used to

be farmland, a brickyard that belonged to the Baltimore Brick Co. and part of

St. Stanislaus Kostka Cemetery, one of several graveyards in the immediate

area. The others included Evangelical Trinity Lutheran Congregational, Mount

Carmel, St. Matthew’s and Oheb Shalom Congregation Cemetery, but the phantom

would show an affinity for St. Stanislaus and often appeared nearby.

Baltimore Row Houses

By the time that the local newspapers realized that

something very strange was happening in the Heights, the panic was almost over.

Most of the stories that remain today come from the back pages of the Baltimore Sun and Evening Sun, which printed a handful of articles between July 25

and July 27, when the sightings came to an end. Reporters approached it as a “tongue

in cheek” story with cartoon illustrations. No one seemed to know when the

events had started, but on July 24, Agnes Martin told a reporter that the

phantom had been seen for “at least two or three weeks.”

The first definite date discovered by researcher Robert

Damon Schneck was on July 19, although the figure had undoubtedly been seen a

number of times prior to that. On this date, though, there was a full moon and

nighttime temperatures were in the 70’s. It was around 1:00 a.m. when William

Buskirk, 20, ran into the phantom. He reported, “I was walking along the 1100

block of Travers Way with several buddies when I saw him on a roof. He jumped

off the roof and we chased him into the graveyard…” One of the other boys

interviewed with Buskirk stated that, “he sure is an athlete. You should have

seen him go over that fence – just like a cat.” The fence that surrounded the

cemetery was six feet in height and trimmed with barbed wire around the top.

According to the witnesses, the figure in black had leapt over it with ease.

Hazel Jenkins claimed that the phantom grabbed her

some time the same week. She saw it twice at close-range and may have been

attacked when the figure tried to break into the Jenkins home (the article isn’t

clear) but her brother, Randolph, saw it soon after. He told a reporter, “I saw

him two nights after he tried to break into our house… He was just beginning to

climb up on the roof of the Community Building. We chased him all the way to

Graveyard Hell.”

The phantom next visited the family of Melvin

Hensler, breaking into their house on July 20, but stealing nothing. After this

unnerving experience, the family went to stay with Mr. Hensler’s brother, but

Mrs. Hensler returned to the house the next day and found “a potato bag left on

the ironing board,” which she was convinced belonged to the intruder. Mr.

Hensler was so exhausted from staying awake that his eyes ached and he had

started talking in his sleep.

Storms on July 23 lowered the temperatures, but had

no effect on the phantom. In fact, on July 24, he was especially active.

Newspapers reported, “At 11:30 p.m. officers Robert Clark and Edward Powell

were called to the O’Donnell Heights area where they were greeted by some 200

people who said that had seen the oft-reported ‘phantom.’ Clark said that they

pointed to the rooftops and someone yelled: ‘The phantom’s there!’” The police

drove around and arrested a twenty-year-old sailor carrying a hammer. He was

fined $5.

A reporter from the Sun found thirty of forty people waiting around the back stoop of a

house on Gusryan Street, waiting for the sun to come up. One of them, Charles

Pittinger, had armed himself with a shotgun. He interviewed several of them,

who passed along rumors and told of their own experiences. Some of them claimed

the phantom lived in the graveyard and a woman who lived on Wellsbach Way,

adjacent to St. Stanislaus, suggested that the phantom was doing more than

jumping fences and breaking into houses: “One night I heard someone playing the

organ in that chapel up there. It was about 1 o’clock.”

The phantom was also reportedly seen beckoning to

Esther Martin from underneath an automobile, saying, “Come here, little girl.”

The consensus of the crowd was that the phantom

easily leaped from two-story buildings, flew over fences and was a general

nuisance in the neighborhood. A man named George Cook admitted having mixed

feelings about what was happening. He did not deny the reports of the phantom,

just the possibility that something extraordinary was involved. In the end, he

blamed the media. “It’s ridiculous to believe that a man can jump from a height

and not leave a mark on the ground. Yet this character does it all the time. It’s

my idea that when this thing is cleared up… it’ll turn out to be one of these

young hoodlums who has got the idea from the movies or the so-called funny

papers, and is trying to act it out. This sort of thing appeals to detective

story readers who are mainly looking for excitement.”

Meanwhile, the police were busy ignoring the

phantom and rounding up the “usual suspects.” On the morning of July 25, they

arrested four boys on disorderly conduct charges at an unidentified cemetery.

Around 10:00 p.m. that same night, officers arrested three boys on an

embankment near the cemetery. Their six companions, all on the lookout for the

phantom, fled the scene. An hour later, the police responded to a call from a

resident who heard footsteps on his roof, but nothing was found. At some point

the next day, Mrs. Mildred Gaines heard the sound of someone trying to break

into her house and ran outside barefoot screaming, “It’s the phantom!” It was

actually the police breaking down the door to serve a search warrant on the

premises. Mrs. Gaines and four male companions were arrested on bookmaking

charges.

By this time, the newspaper coverage – which had

started off with reporters as baffled as the residents of O’Donnell Heights –

turned humorous. The stories poked fun at the sightings, reported pranks by

neighbors pretending to be the phantom, and carried a story about a phantom

sighting on a rooftop that turned out to be a ventilation pipe. On July 27, the

Evening Sun announced there were no

more reports and that, “Police think it might be a teenager.” The phantom was

gone, but the heat was back, with high humidity and temperatures in the middle

90’s.

Like most bizarre “flaps” of this type, there was

no satisfying resolution to the panic created by the Phantom of O’Donnell

Heights. An unofficial version claimed that residents finally chased it into

the cemetery, where the phantom jumped into a crypt and vanished for good.

No one can say who, or what, this figure may have

been, although based on the sheer number of sightings, something weird was happening in the neighborhood. Descriptions of

the phantom were fairly consistent, considering that that the encounters were

brief, took place in the dark, and he was usually moving at a good clip.

William Buskirk said, “He was a tall thin man dressed all in black. It looked

like he had a cape around him.” The only one who mentioned the phantom’s face

was witness Myrtle Ellen, who said it was horrible. She also agreed about the

dark costume. The newspapers described the phantom as “black robed,” suggesting

long, loose-flowing clothes. Mrs. Melvin Hensler, discoverer of the discarded

potato sack, saw the phantom three times and said that during one sighting, it

looked as though he had a hump on his back.

Theories abound about the “Horror of the Heights.”

Sociologists have described the events in O’Donnell Heights as an example of an

“imaginary community threat,” suggesting that the 900 families living there

experienced some type of mass hysteria, whipped up by rumors and the media. It’s

true that misconceptions undoubtedly played a part in the events, but they don’t

explain the relatively straightforward experiences described by William Buskirk

and other witnesses. The police never denied that people were seeing something

but, like George Cook, thought it would turn out to be a “young hoodlum.” But

if it was, he was never caught, exposed or confessed.

It’s also hard to accept that the newspapers played

a part in creating any hysteria. The two local papers ran only six articles on

the phantom, two of them mere fillers, and they were printed as the sensation

was coming to an end. The only one that might be called “sensationalistic” ran

on July 25 and included the experiences of a number of witnesses. However, it

ended on a sober note: “The question of the prowler of O’Donnell Heights

continued to be not one of the phantoms, but of people reacting to (and

possibly creating) the unknown with their imaginations.”

Some have taken the phantom’s affinity for St.

Stanislaus as evidence that it was an actual ghost. Part of O’Donnell Heights

was built on land that once belonged to the cemetery, which contains a great

many unmarked graves from the influenza epidemic of 1918. Also, bodies were

exhumed and reinterred when Boston Street was extended in the 1930s, but it’s

hard to see how this would stir up a spirit in July 1951.

There has also been the suggestion that the phantom

was some sort of mysterious entity like the “Mothman” of West Virginia or the “Mad

Gasser of Mattoon,” which plagued a small town in Illinois in 1944.

Whatever it was, it remains a mystery and one that –

like far too many others – will simply never be solved.

No comments:

Post a Comment